Originally posted on The Whole Sky.

I later found the site “Mama Bear Effect” which I think is a good, evidence-based guide to practical actions to reduce risk.

Content: nothing graphic. Discussion of adults not believing children.

I think this is a good thing for non-parents to read too, since neighbors, teachers, and family friends may be in a position to notice something is happening.

A while ago a relative expressed worry about the possibility that her child might be sexually abused in the future. Other adults in the family assured her that children are very safe nowadays and that there was almost no risk.

As someone who works with sex offenders, and as the parent of a little girl, this question interests me a lot.

I think it’s important to know the actual risks, because in the past programs have been aimed at preventing risks that weren’t particularly likely: stranger rapes by “predators.” You don’t want to frighten people about events that are very unlikely, but you also don’t want to ignore more likely risks.

How common is it?

- It’s notoriously hard to collect good data on this, but a metastudy concluded that the sexual abuse prevalence rate for girls in the US is 10.7% to 17.4% and the rate for boys is 3.8% to 4.6%. This is for contact abuse only (abuse that involved touching, not something like an adult showing their genitals to a child).

- Sexual abuse rates seem to be declining, probably because of greater public awareness and less tolerance of abuse.

Characteristics of children at risk:

- Risk factors, in order of magnitude: being a girl, having low socioeconomic status, and not living with both biological parents (foster children are most at risk). There are racial differences but they all disappear when you control for class and family structure (source). Other risk factors include being socially isolated, not having someone to confide in, having a mother who is dead or mentally ill, and having parents with alcoholism (source).

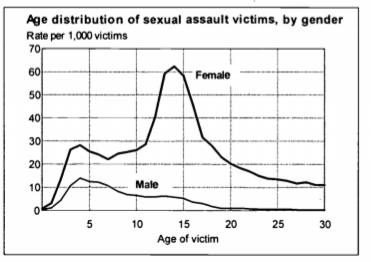

- Boys are most at risk as very young children (peaking around age 4), and less at risk as they get older. Girls’ risk peaks once around 4 but rises to a higher peak around 14.

(source)

Characteristics of perpetrators:

- Perpetrators are usually a family friend, neighbor, or babysitter. Family members are next most likely, with strangers being fairly unlikely (14%).

- Different sources estimate that 87% to 95% of perpetrators are male. (source, other source)

- About a quarter of the time, the perpetrator is under age 18. 14 again seems to be a particularly risky age. I’m not sure how much of this pattern is 14-year-olds assaulting other 14-year-olds (or how much the 14-year-olds would consider consensual, or how much a 14-year-old can consent).

How do you find out?

- Sexually abused children usually don’t tell anyone during childhood (source).

- If children disclose abuse, they are most likely to tell their mothers and adolescents are most likely to tell a friend. Teachers are third most likely. (source) To me, this points to the importance of having a relationship where your children trust you. I’ve heard horror stories from clients about not being believed, or even being beaten, when they told their parents they were being molested. This made no sense to me until I reflected that the abuser was usually a respected person like the mother’s brother or the parish priest. I also think parents are sometimes so overwhelmed by horror at the thought of this happening to their child that they refuse to believe it.

- Rather than giving one complete disclosure, children often drop a hint, see what the reaction is, and then decide whether to drop more hints. To me, this again underscores the importance of paying attention to what children say and responding sensitively.

- It’s fairly common for children to recant or change stories after disclosing abuse, presumably because the memories are difficult to deal with or because it’s causing a stressful situation. (Imagine a child who discloses first to a sibling, then to her mother, then to the child protective worker, then to the police investigator, then a taped deposition for the court—she may recant just to make it all stop. Some families choose not to press charges for this reason.) Memory lapses are also a post-traumatic symptom, and it’s possible some children genuinely don’t remember. I have no idea how you tell the difference between the retraction of a false story and a true one, but it’s considered very unlikely that a child would make this up.

- Sexual drawings and age-inappropriate sexual behavior may be an indication that something has happened.

Protecting children:

These are my personal guesses, not proven strategies. Some other ideas here.

- Listen to children. Pay attention to their fears and concerns.

- Drop in unexpectedly when children are alone with an adult or an older child. Offenders are rarely caught in the act but are often caught pushing boundaries.

- Notice your child’s mood after they have been alone with an adult or older child.

- If your child seems uncomfortable around someone, err on the side of keeping them apart even if you haven’t gotten to the bottom of the situation.

- Make clear to children that they will not be blamed for disclosing and that sexual abuse is never children’s fault.

- Respond with support and love if they disclose something. Let the child know you appreciate their bravery in telling, and that it is now your job to handle the situation. More good tips here and here.

- If you hear a disclosure, you will probably experience shock, rage, and sadness. Try to stay calm around the child—let them see that you can handle hearing this. Find an adult you can vent to, so the child does not have to take care of your emotions.

- Respect children’s boundaries. Don’t make them hug or kiss people they don’t want to, even if grandma is expecting it. In a discussion on boundaries at a Quaker community where I lived, one woman recounted that when she asked a six-year-old girl in the community for a hug, the girl answered, “I only hug people in my family.” The woman held this up as healthy development to be celebrated. Teaching children phrases like this, or a simple “No, thanks,” teaches children that it’s fine to refuse unwanted attention.

- Unfortunately it’s unclear how well any of this works.